Making a Living on the Farm

(View Contents)

Cassidy Lake is rural farmland. The nearest village, Norton, where there is a rail station, is 9 miles, the nearest town, Sussex, 15 miles away, and the nearest city, Saint John, 40 miles away. Making a living there was challenging. Studying the family history we conclude the Cassidy family, like their neighbors, weren’t rich, but they weren’t poor either.

The Port in Ireland where William grew up was a poor fishing village of about 50 residents. Here the Cassidys were shipbuilders and carpenters, not fisherman or farmers. We believe William and Jane probably brought a little money with them to Canada in 1819 by virtue of the fact they bought property at the head of Kings Street in Saint John shortly after they arrived. [We have not been able to find any record of William and Jane owning property in Saint John in that time period.] It’s pretty certain it was not a lot of money they brought with them because, four years later in 1823, William had to take out a loan of £40 (the equivalent of about $5,000 today) to purchase 150 acres at Cassidy Lake.

So how did they make a living at Cassidy Lake? The Cassidys of Cassidy Lake were an energetic and creative lot and they needed to be. While we refer to the homestead as a farm, as farmland goes it is not great. The land is hilly and rocky with only a fairly thin layer of topsoil much like The Port area they left back in Ireland. Thus, Cassidy Lake does not lend itself to large acreage farming. It’s interesting to note that William came from a family of shipbuilders, carpenter and cabinet makers, not farmers. Therefore it is not surprising that the family income came from a variety of sources. We get a good insight into the accounting detail of their lives from accounting records they kept of farm and cheese factory operations in the early 1900s. The “STOP Book” as it is titled, is an interesting collection of notes and financial transactions made by initially by Francis Edward Cassidy and later by his son, Robert Allen Cassidy. Multiply these amounts shown below by 13 for an approximation of the value in today’s dollars.

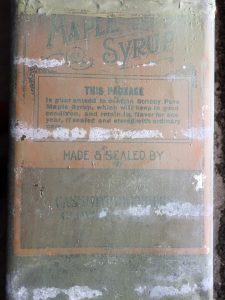

Farm business activities were not “mom and pop” operations. As evidence by the label on the maple syrup can, they understood marketing principles “Made and Sealed by Cassidy Brothers, Clover Hill”. How they picked the name Cassidy Brothers for their enterprise is unknown but it shows they understood the importance of presenting a profession image to the public. The maple syrup can label shown here was provided by Amanda Douthwright who discovered it while renovating the Pollock home in 2017 which Matthew Cassidy had built in the early 1900s. The maple syrup can was being used as a vent.

Farming

Mixed farming was the model at Cassidy Lake. They had a the usual cows, pigs, chickens and ducks. In later years they added geese. None of these animals were raised in great numbers but were sufficient for the family’s food needs and to sell in the local market. One limiting factor was the need to provide shelter during harsh Canadian winters. The barn had room for about 20 cattle plus a few pigs during the winter. Corps consisted of the usual garden vegetables as well as oats and buckwheat which were essential sources of feed for the horses and other farm animals. The following excerpts from the farm accounting book section Account of Cows and Other Stock show how much income they received from the sale of:

| 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | |

| Milk | $881 | $735 | $439 |

| Cream | 295 | 369 | 314 |

| Pigs | 300 | 284 | 285 |

| Veal Calves | 75 | 91 | 75 |

| Beef Cows | 212 | 50 | 118 |

| Heifers | 125 | ||

| Maple Syrup | 75 | 75 | |

| Apples | 10 | 18 | |

| Potatoes | 25 | 144 | |

| Oates & Buckwheat | 25 | ||

| Total | $1898 | $1891 | $1242 |

For some reason, income in this category dropped significantly in 1921. Any expenses they had associated with this activity would need to be deducted, but there probably were not many. In April 1920 they bought six pigs for $38. These are the only associated expenses listed.

Another income category is Account of Hens which brought in:

| 1919 | 1920 | |

| Eggs | $162 | $177 |

| Roosters | 15 | 3 |

| Chickens | 50 | 47 |

| Pullets | 14 | |

| Hens | 7 | 34 |

| Ducks | 2 | |

| Total | $252 | $261 |

Eggs sold from $0.37 to $0.70 per dozen, the price being higher in the winter months. There are no expenses associated with this activity. It is interesting to note there are several entries of chickens, rooster, and hens marked as “ate” as opposed to “sold”. Does this mean a chicken that ends up on the family dinner table is recorded as a sale? No eggs are marked as “ate” nor are any items in the Cows account so the meaning of “ate” is a mystery.

A large number of individuals in the area had accounts with the Cassidys. One example is that of Arthur Barrett in 1931:

| April | One ton hay | $14.00 |

| May | One ton hay | 14.00 |

| June 1 | Trip to Sussex with car | 3.00 |

| June 15 | Trip to Titusville with car | 3.00 |

| Total | $34.00 |

Mr. Barrett paid for his purchases over time as follows:

| April 29 | Cash | $10.00 |

| July 10 | Cash | 5.00 |

| Sept 29 | Cash | 10.00 |

| Feb 12 | Cash | 5.00 |

| July 21 | Cash | 4.00 |

There was also income from renting out the pasture. On May 24, 1929, Robert Monahan put 3 yearlings in the pasture, on June 1, Duncan McLong put 8 head of cattle in the pasture, and on July 10, Frank Baxter put 5 head of cattle in the pasture. There is no indication of how much they paid for using the pasture.

Lumbering

Trees on the farm were a good source of hard and softwood. Besides providing lumber for construction of the homestead buildings and church, they were a source of wood for furniture the Cassidys made and sold. Logs cut on the farm were hauled to a mill at Upham for cutting into lumber. Stan talked of using a team of horses and sled to haul loads of logs in the winters of the 1920s. Much of the lumber was then hauled to Norton for shipment by rail to customers.

Lumber was sold to wholesalers and to individuals. We see records of carloads being shipped to markets in places like New York and Boston. For example

| June 26, 1922 | Car #13229 Grand Trunk 2X3 Spruce 16,349 ft | $320.11 |

| July 15, 1922 | Car #70204 Pere & Maraquette 2X4 Sized 20,040 ft | $380.10 |

| July 15, 1922 | Car #67701 Boston & Maine 2X6 14,998 ft | $275.75 |

| Aug 30, 1922 | Car #199735 New York Central 2X4 Sized 12,100 ft. | $198.55 |

| Dec 11, 1922 | Car #10499 N.Y. 13,966 ft | $293.14 |

Furniture and Cabinet Making

This was a good source of income. They had a good size workshop attached to the barn which included a foot-powered wood lathe that was still operational in the 1940s. We see examples of their handiwork in the church windows and furnishings. It is interesting there are no entries for this type of work in the accounting record. This may be due to the fact that this record starts in 1916 when Robert Allen was running the farm. While his father, Francis Edward was a skilled cabinet maker as were some of his sons, Robert Allen was not.

Cheese Factory

The cheese factory was probably the family’s biggest enterprise. It was a co-op arrangement. Farmers supplied the milk for cheese making and were paid according to the profits from cheese sales. We get an idea of the scale of the cheese factory operations from the 1919 results.

| Milk Received | 343,926 lbs |

| Cheese Made | 33,014 lbs |

| Total value of Cheese made | $9231.46 |

| Total cost to manufacture | $907.89 |

| Proceeds coming to patrons | $8323.57 |

A portion of this proceeds would go to the Cassidys based on the milk they provided.

Allen Cassidy was paid at the rate of $2.50 a day when he worked in the cheese factory. In 1919 he earned $34.50. He was also paid $4.00 when he hauled wooden boxes for the cheese from Norton. He was also paid $4.00 for a trip to Sussex to get the car fixed. This implies the family car was a cheese factory business expense.

In 1921 the cheese maker was paid $100/month for 5 months work. A helper $25/month for 1 ½ months and the secretary (Allen Cassidy) a salary of $50. In 1924, the secretary’s salary was increased to $100.

Financial Services

It appears Allen Cassidy carried notes for people in the community. Exactly how this worked is not clear. In 1926 Robert Allen had 33 notes at the Provincial Bank in Norton and 30 notes at the Royal Bank of Canada in Sussex. The loans were all for 3 months and ranged in value from $30 to $100 with the majority being in the $30-$50 range. Included in the list of note holders were F.E. Cassidy, Robert Allen’s 92 year old father, Robert Allen’s wife Edith, and their son, Stanley, age 14.

Public Employee

Robert Allen Cassidy was School Superintendent for a time and we see many entries for School Tax in people’s accounts. In addition to a salary as School Superintendent, Allen would profit from handling the payment of people’s school taxes. It appears that he paid the tax and which he collected from the individuals.

Telephone Service

The Cassidy farm had a telephone. It was assumed the telephone was there as part of the cheese factory operation. However, given how detailed the expense records were for the cheese factory and the fact that telephone does not show up as an expense for factory operations in any year, this assumption is probably wrong. In any case, locals used the phone were charged to make calls. The rate was not cheap. Some examples:

| Apr 29, 1917 | Fred Tuibe | Telephone to Norton | $0.45 |

| Jun 2, 1917 | Andrew Campbell | Telephone messages | $1.10 |

| Jan 2, 1918 | Thomas Brown | Telephone to Norton | $0.45 |

| Aug 25, 1919 | Hubert Tabor | Telephone message | $0.45 |

| Oct 5, 1921 | Matthew Cassidy | Telephone to Norton | $0.45 |

| Feb 15, 1922 | Charles McCarron | Telephone message | $0.75 |

| Jun 9, 1922 | Charles McCarron | Telephone | $0.25 |

| July 7, 1922 | Matthew Cassidy | Telephone to Petitcodiac | $0.55 |

Other Opportunities

The Cassidys were not reluctant to take on projects. A good example is when a Capital Airways plane made a forced landing on Cassidy Lake in February 1940 due to engine failure. On Feb. 23, Robert Allen was paid $2.00 for logs and work to construct a derrick to change the engine. On Feb 24 he received $4.00 to haul the engine to Norton, and another $4.00 on March 20 to haul the engine from Norton to Cassidy Lake. In addition, between February 22 and March 22, they provided 33 meals for the people working on repairing the plane. The accounting entry says meals, but it’s a safe assumption this included sleeping accommodations as well.

There is no indication of what the charge was for the meals but borders at the homestead paid $4.50/week in 1922.